Exemplary Teaching Award in General Education 2022

This year, seven teachers were nominated for the Exemplary Teaching Award in General Education and the awards go to

1. Dr. Lau Po Hei of the Office of University General Education

2. Professor Gordon Mathews of the Department of Anthropology.

Ceremony

Date: 24 August 2023 (Thursday)

Time: 3:30 p.m. – 5:15p.m.

Venue: LT9 , Yasumoto International Academic Park (YIA), CUHK

Dr. Lau Po Hei

Dr. LAU Po Hei obtained his undergraduate, MPhil and Doctoral degrees in Philosophy from the Department of Philosophy at The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK). In 2012, he joined the Office of University General Education of CUHK. He has taught the General Education Foundation course, UGFH1000 In Dialogue with Humanity. Dr. LAU is also a part-time lecturer in the Department of Philosophy at CUHK, teaching courses such as UGEA2150 Chinese Culture and Its Philosophies and UGED2891 Philosophy of Love. From 2017 to 2020, he was an assistant professor in the Department of Philosophy at Soochow University in Taiwan.

His research interests are Confucianism, modern Chinese philosophy, and comparative philosophy. He co-edited a volume on the teaching of general education: World in Words: Humanities Classics and General Education (2021).

“As we learn, we discover our limitations; as we teach, we encounter difficulties;

both can inspire self-reflection and self-improvement.

Therefore, it is said that: The interplay between teaching and learning is reciprocal.”

- “The Book of Learning” in The Book of Rites

The General Education (GE) courses that I have taught are all in the humanities. I believe that the humanities serve to deepen our understanding of the self and the world around us.

Reflection is at the heart of my teaching philosophy. The starting point of the study of humanities is that we do not quite understand how we acquire knowledge about ourselves and the world. We do not fully understand how we come to have ideas and experiences, and how these relate to our human faculties and dispositions; additionally, we lack a complete understanding of how human society is formed. The study of humanities helps us to understand ourselves by reflecting on the concepts we use, and the conceptual frameworks within which we think about various things. By engaging in reflection, we are able to question our assumptions, challenge our biases, and cultivate a more comprehensive and nuanced perspective on the complexities of human experience.

Reflection does not start from nothing. There is always a story behind our reflection - a history that has shaped the way we think today. If we do not reflect, we will be blinded by the present moment. From a historical perspective, we know at least two things: First, the finitude of human experience. Prior to any conscious choice, the concepts, customs, and institutions in our daily lives have already been given to us. Second, the possibility of human experience. The fact that humans exist in this way may be a historical accident. If the concepts, customs, and institutions are all artificially created, it means that human experience can be this way or that way. In this sense, the use of a historical approach in the study of the humanities represents a form of liberation. One can transcend the limitations of one’s own time and place and attain a broader perspective on the cultural forces that have shaped us.

I also owe much of my understanding of reflection to the Socratic method, which involves questioning the assumptions of others through a dialogue format. For Socrates, philosophy is distinctly different from science; philosophy does not rely on experimental or empirical observation, but purely on reflection. By “reflection,” in my view, refers to a detached perspective on the subject matter at hand, avoiding conformity to convention or habit. Socrates believed that reflective activities are inherently social, rather than individualistic. He asked questions from a social perspective, with a focus on social and political order, and the moral character of political leaders. Dialogue is one of the best ways to achieve this, as it allows for the collision and exchange of ideas. Therefore, the Socratic method requires more than solitary reflection in a library or in one’s own mind; it involves engaging with others in the public sphere. As Socrates did with his interlocutors, my aim is to encourage my students to engage in discussions with others in an open-minded way. Socrates’ interlocutors are expected to be sincere about their beliefs, to examine how those beliefs fit together, and to show respect for their companion. These valuable lessons from Socrates, after all, offer much to be learned.

Professor Gordon Mathews

Gordon Mathews is a Research Professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, and is the incoming Chair of the World Council of Anthropological Associations. He has written the books What Makes Life Worth Living? How Japanese and Americans Make Sense of Their Worlds (1996), Global Culture/Individual Identity: Searching for Home in the Cultural Supermarket (2000), Hong Kong China: Learning to Belong to a Nation (2008, with Lui Tai-lok and Ma Kit-wai), Ghetto at the Center of the World: Chungking Mansions, Hong Kong (2011), The World in Guangzhou: Africans and Other Foreigners in South China’s Global Marketplace (2017, with Linessa Dan Lin and Yang Yang) and Life After Death Today in the United States, Japan, and China (2023, with Yang Yang and Miu Ying Kwong). He has been teaching a weekly class of asylum seekers in Chungking Mansions for the past fifteen years. He also composes and performs electronic music: https://www.youtube.com/@gordonmathews2647/videos.

I am 67 years old, and am retired, though I am still teaching four General Education courses each year as a research professor. I have long wondered if, as I grew older, I would lose touch with students. Judging from my course evaluations, this has not happened yet, for which I am grateful.

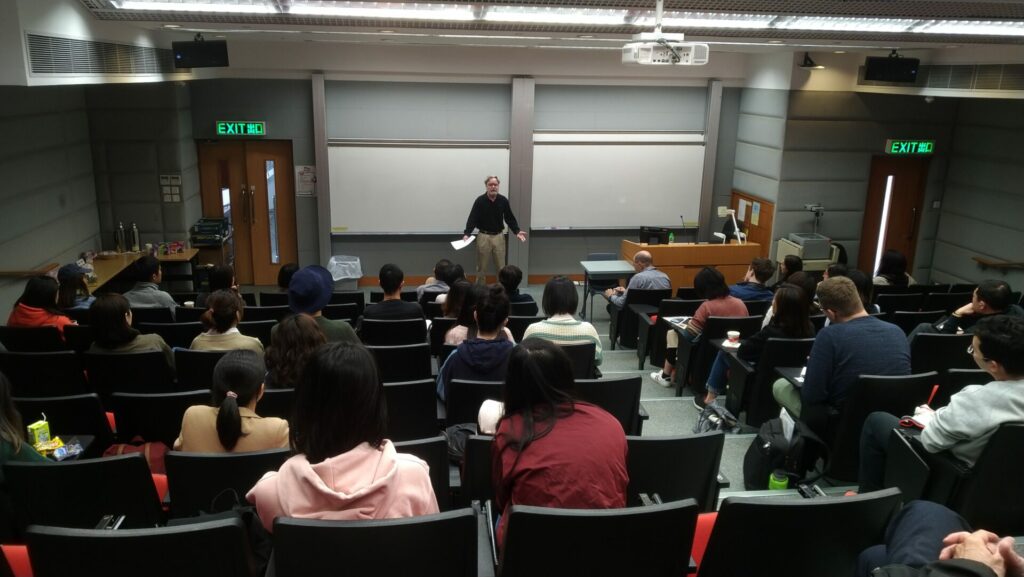

The keys to successful teaching in my view are 1) to believe that what I am teaching is of critical importance for students in gaining an education that will provide them with insights throughout their lives; 2) to teach with great enthusiasm, as well as care and compassion for students in their efforts to obtain understanding; and 3) to make education in the classroom a two-way rather than a one-way process, in which students are engaged in extensive questioning and discussion rather than simply listening to me. As for the first of these keys, I have shaped the General Education courses I teach — “Meanings of Life”, “Globalization and Culture”, “Humans and Culture,” and “Culture of Hong Kong”— to deal with fundamental questions of life, questions that I myself wish I would have been exposed to when I was a student. As for the second of these keys, I am enthusiastic by nature, but I make considerable efforts to relate to students: learning most of their names in large classes, and learning about them as people. As for the third of these keys, I ask a number of provocative questions in my classes, ranging from “Why are human beings so afraid of death today?” to “Is patriotism good or bad for the world?” to “Why does foul language so often invoke sex? Isn’t sex about love?” to “What do you think is the future of Hong Kong?”. We discuss these questions at length — I offer my own views but stress that students are free to think and express as they choose as long as they use logic and have evidence for their views.

The general rule I follow in my classes is that I should lecture for no more than 60% of class time. The remainder of the time consists of students offering their informed views and asking questions; this encourages students to think for themselves; and indeed they do. I can succeed at this by carefully reading students’ faces and body language. Hong Kong students, and Asian students in general, do not like to raise their hands; but by observing their expressions and eye contact with me, it is clear who would like to speak up — I can call on them and they indeed offer valuable questions and comments. Involving students this way is deeply important in my teaching: students make the class much better by asking questions about issues that I have not adequately explained, and by bringing in perspectives that I myself do not share but that definitely deserve to be heard. Rational discussion using critical thinking, where we can all learn from one another, is the essence of university learning, and this is what I strive for in my classes.

I do not teach in order to get good course evaluations, and sometimes provoke students in ways that cause me to have less good course evaluations — course evaluations are many magnitudes less important than students’ own growth into becoming critical thinkers and responsible citizens in their adult lives. But I nonetheless feel deeply gratified that students appreciate my efforts to teach my classes well. I have felt a deep love for my students over my decades of teaching, and when I leave teaching, as I will before too many more years, I will miss them enormously.